FAQ

The known chemical formula of Australian opals is SiO2nH2O,this shows that opals are made of a non-crystalline form of silica that contains some parts water, among other very small trace elements of minerals depending on the ground it’s mined from to produce its overall chemical makeup. Silica is a major constituent of sand which is believed to be the reason as to why Australian opal can produce such stunning colours. This can be explained as the same as when light refracts through a glass prism, the light refracts through the opal and rebounds all levels of the colour spectrum. The most important time in which the formations of opal began in Australia is during Cretaceous period up to the Quaternary period approximately 150 million to 60 million years ago. During these periods there was mass changes happening within the earth’s crust, the sedimentary process in which opal was formed was due to the fact the earth’s crust continued to build layer upon layer. Oceans continued to rise, lakes, rivers and lagoons formed through out various regions of Australia and at one stage a shallow inland sea covered much of inland Australia where majority of opal fields are found today. These rivers and seas that spanned through out Australia allowed for water to seep through cracks and faults in the ground and pool in catchment areas under the ground allowing for opal to form. It’s estimated that it may take up to 5 million years to form 1cm of opal, showing how valuable opal truly is.

Where are opals found in Australia and throughout the world?Opals in Australia are found in isolated areas where a shallow inland sea stretched from the gulf of Carpentaria, Queensland (QLD) down through New South Wales (NSW) to South Australia (SA) anywhere up to approximately 150 to 60 million years ago. Some of the most noted mining fields in QLD include Eromanga, Yowah, Opalton, Quilpie, and Winton. Queensland mining fields are best known to produce boulder and matrix opal due to the specific rock formation known as ironstone. New South Wales holds one of the most notable mining field areas in‘Lightning Ridge’ which predominately produces the world renown black opal, another area of note in NSW is the White Cliff mining field. South Australia’s highly well-known mining field is Coober Pedy, which produces white and crystal opal, other mining fields include Mintabie, and Andamooka which produces matrix opal. Overall Australia produces approximately 95% of the world’s opals.

Other countries that produce opal include Ethiopia, Brazil, Mexico and Mali for example, however there is varying quality due to the formation and composition of opal found in these regions. For example, Ethiopian opal which forms predominately within weathered layers of rhyolite or volcanic rock which can be porous and more susceptible to water damage.

What type of opals are available within Australia?In Australia the predominate opals of gem value include the following:

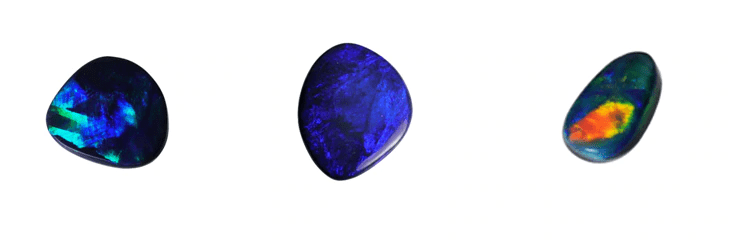

Black opal – Given the name due to having a bar of gem colours over a black or dark background. Black opal is considered one of the most valuable opals available due to the fact the black or dark background helps bring out the brightness and strength in the colours. Black opal is most notably mined in ‘Lightning Ridge, NSW’.

Examples of Australian Black Opal

Black crystal opal – Has a smokey semi-transparent background that delivers high quality colours and value due to having a darker body tone in comparison to crystal opals, this darker body tone helps bring out the vibrant colour spectrum that opals have to offer. Some circles consider black crystal opal alongside the black opal in value and desire due to the ability to bring out the strength and brightness in colours.

Examples of Australian Black Crystal Opal

Grey opal – Varying in colour from light grey to a nearly black background, can also appear smokey or cloudy on occasions. Grey opal sits in between white and black opal in relation to body tone, colours can be very bright when sitting on dense semi-black backings of potch (colourless opal) and provide strong colours that are very desirable.

Examples of Australian grey opalMilky or white opal – An opal with the same gem colour range seen through all other Australian opals but has a milky or white background. White opals don’t have the advantage of the black or boulder opal body tone which enhances the strength of the colour, however there are still fantastic white opal pieces available that has vibrant colour. White opal is most notably mined in South Australia.

Examples of Australian White Opal

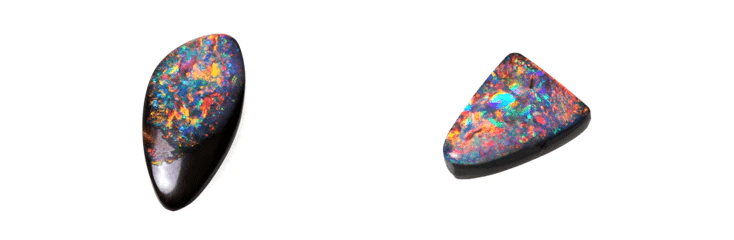

Boulder opal – Formed only in Queensland due to the ironstone. Boulder opal is often cut with the ironstone as a backing to allow the stone to be darker and hold the beautiful colour, this makes it a highly valuable type of opal. Boulder opal can display any range of vibrant colours on the colour spectrum and is generally produced in thin veins of ironstone ranging from millimetres to centimetres in thickness.

Examples of Australian Boulder Opal

Matrix boulder opal – Known for its vivid pin flecks of colours, almost looking like stars in the night sky. Matrix is a porous sedimentary ironstone that has minute cavities filled with precious opal that is most commonly found in QLD, not to be confused with Andamooka matrix which is found in South Australia and soaked in a sugar solution then boiled in acid or heated in an oven to give it a darken appearance.

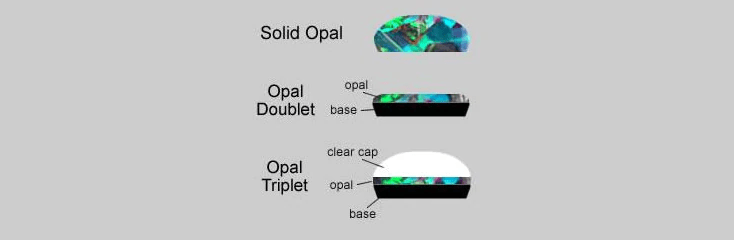

Doublets & Triplets – Is a combination of a piece of opal glued with an epoxy resin to a black backing usually potch (colourless opal) or colourless boulder (ironstone) to allow the piece to be stronger, thicker in size and to bring out the quality in colours that opals supply. When creating a doublet both the rough gem quality opal and rough potch/boulder are adhered together and cut in the same manner as cutting a solid opal. Triplets go through a similar process but also require a glass capping or a clear piece of quartz over the opal layer to help protect the layer of gem quality opal, enhance the colours of the stone and give the piece a cabochon (domed) look. Doublets and triplets aren’t as valuable as solid stones due to having a thinner slice of opal, but it allows for everyone to own there very own piece of this rare gemstone at a fraction of the price, while still supplying beautiful, vibrant colours that opal has to offer.

Difference between solid opal, doublet opal and triplet opal

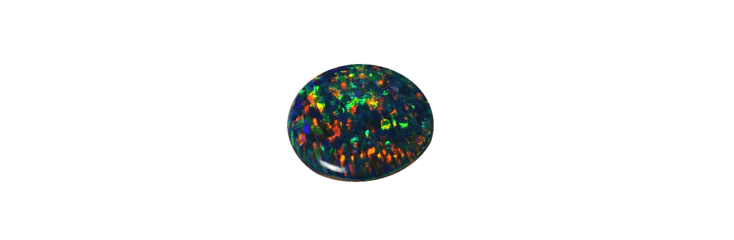

Unfortunately, opals can be faked, and they’re beginning to appear much more like natural opal. The most common synthetic or man-made opal is known as Gilson opal. Gilson opals are chemically produced in a laboratory using the same components of natural Australian opal, silica,this makes it difficult to detect using a gem tester. Nevertheless, to the trained eye, it can be identified if you look for certain key points. Gilson or man-made opals are generally too perfect or too uniform regarding colour strength and pattern, whereas natural Australian opals has a varying pattern and colour strength throughout the piece. Another give away is that Gilson opal generally has a snake like pattern throughout and will be cut into a perfect oval, circle with a nice cabochon(dome) due to coming out in a man-made block in the lab,in comparison to natural opal which is generally free form due to being produced by nature. However, it’s good to note the shape of the opal is not a key factor in detecting if an opal is a real or not as natural opal can be cut into oval, circle or with a high cabochon if the rock formation allows.

Example of Gilson (fake) opal – Notice the snake like pattern, uniform colour strength throughout and overall too uniform, too perfect

In a cave in Kenya, Louis Leakey, the famous anthropologist, uncovered the earliest known opal artifacts. Dating back to about 4000 B.C., they most likely came from Ethiopia. Historically, opal discoveries and mining progressed similarly to the ways diamond, emerald, ruby and sapphire were produced. As early humans found various gemstones, they slowly learned to work them into decorative shapes. As communities developed, gems became symbols of wealth.

In the Old World, Hungary mined opal for Europe and the Middle East, while Mexico, Peru, and Honduras supplied their own native empires with the gemstone. Conquistadors introduced New World opal to Spain when they returned with stones in the early sixteenth century.

Since the late 1800’s, Australia has dominated opal production with more than ninety per cent of the global output. Opal of differing qualities occurs in more than twenty other countries, including Zambia, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Poland, Peru, Canada, New Zealand, Indonesia, the USA, Brazil, and Mexico.

The modern name of the gem opal is derived from ancient sources: the Sanskrit Upala – which means “precious stone”; the Latin Opalus; and the Greek Opallios which both mean”to see a color change”.

Early races credited opal with magical qualities and traditionally, opal was said to aid its wearer in seeing limitless possibilities. It was believed to clarify by amplifying and mirroring feelings, buried emotions and desires. It was also thought to lessen inhibitions and promote spontaneity. The early Greeks believed the opal bestowed powers of foresight and prophecy upon its owner, while in Arabian folklore, it is said that the stone fell from heaven in flashes of lightning. To the Romans, it was considered to be a token of hope and purity.

Ancient Romans provided the first real market for opal. With a rich powerful empire, wealthy citizens acquired disposable income and a passion for gems. Opal, whose colours changed with every shift of light, was rarer than pearls and diamonds and destined to be the stuff of myths and dreams.

Mark Antony loved opal. Indeed, it is said that he so coveted an opal owned by Roman Senator Nonius that Mark Antony banished the Senator after he refused to sell the almond sized stone, reputed to be worth 2,000,000 sesterces. (US $80,000) Mark Antony is said to have coveted the opal for his lover, Cleopatra. Legend states that one Roman Emperor offered to trade one-third of his vast kingdom for a single Opal.

Writing before his death in 79 A.D., the Roman Pliny wrote of the opal as “Having a refulgent fire of the carbuncle (ruby or garnet), the glorious purple of amethyst, the sea green of emerald, and all those colours glittering together mixed in an incredible way.”

Pliny thought the opals came from India, but the gems so eagerly sought by Rome probably came from open cut mines in Hungary, situated near Cervenica or Cernowitz (now Czechoslovakia). He had been deceived by dealers who had probably hoped to capitalise on the appeal of “oriental” imports. Hungarian opals have a milk-white background, usually with a pin-fire, small-size colour display. During the Middle Ages, more than three hundred men worked the mines in Hungary. The mines in Eastern Europe were the only source of European opal until the Spaniards returned from the New World with Aztec opal.

In the Middle Ages, the opal was known as the “eye stone” due to a belief that it was vital to good eyesight. Blonde women were known to wear necklaces of opal in order to protect their hair from losing its color. Some cultures thought the effect of the opal on sight could render the wearer invisible. Opals were set in the Crown jewels of France and Napoleon presented his Empress Josephine a magnificent red opal containing brilliant red flashes called “The Burning of Troy.”

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, opal began to fall out of favour in Europe. It was wrongly branded as bringing ‘bad luck’, and was associated with pestilence, famine and the fall of monarchs. Queen Victoria, however, did much to reverse the unfounded bad press. Queen Victoria became a lover of opal, kept a fine personal collection, and wore opals throughout her reign. Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester, gave an opal ring to her niece Queen Victoria in 1849. This opal ring had been previously owned by Queen Charlotte since about 1810.

Queen Victoria’s friends and her five daughters were presented with fine opals. Opal became highly sought after because the Royal Court of Britain was regarded as the model for fashion around the world and fine quality opal had recently been discovered in far-off Australia. In the latter years of Queen Victoria’s long reign, various Australian opal fields were discovered and worked.

The first discovery of common opals in Australia was made near Angaston (SA) by the German geologist Johannes Menge in 1849. Both the Queensland Boulder Opal and Lightning Ridge fields attracted miners in the 1880’s. Production of precious opal began at White Cliffs (NSW) in 1890, from Opalton (Qld) in 1896, and at Lightning Ridge (NSW) in 1905.

Before 1900, rough opal was sent from White Cliffs, the premier NSW opal field, to Germany to be cut and polished. Gradually, professional cutters began appearing on the fields. They rigged up old treadle sewing machines or bicycles, designing innovative cutting/polishing gear. In 1907 at Old Town, on the Wallangulla Opal Fields (later known as the Lightning Ridge Opal Fields), the first recorded cutter was Charles Deane. When the 3-Mile broke out in 1908, cutters worked at Nettleton on 3-Mile Flat. Lorenz had learned to cut in Germany. He used horizontal wheels with a hand crank and was an expert. He made doublets, jewellery, and was one of the first to buy opal by the carat. Many miners cut their own opal, and often very roughly.

A study of the many written accounts of the time suggests that most of those early Australian discoveries were accidental – a horse’s hoof kicked up opal-bearing rock, a boundary rider’s wife discovered a pretty pebble in a creek bed, a flock of sheep was struck by lightning during a rainstorm and the run-off from the storm uncovered opal at ‘Lightning Ridge’. A number of Queensland locations also came into their own during the Depression years, when men without work were willing to chance their luck.

When Australian opals appeared on the world market in the 1890’s, the Hungarian mines spread the idea that it was not genuine, probably because gems with such brilliant fire had not been seen before. By 1932, the Eastern European mines were unable to compete with the high quality stone being produced in Australia and ceased production, allowing Australia to assume the mantle of premier opal producer of the world, becoming famous for Lightning Ridge’s colourful and rare black and crystal stone.

In South Australia, Angaston was followed by Coober Pedy in about 1912, Andamooka in about 1930, and then Mintabie. During the depression of the 1930’s the industry declined until new finds in 1946 stimulated mining and, since then, there has been a spectacular increase in production. Now over 50% of world production comes from South Australia.

A HISTORY OF OPAL MINING IN QUEENSLANDThe history of opal in Queensland is one of heartbreak, frustration, determination and at times success at incredible odds. Rich in myths and legends, Queensland is the birthplace of the Australian Opal Industry. Opal was first discovered in Queensland on Listowel Downs, south of Blackall in 1869. The first registered mine was in 1871 south of the present town of Quilpie. Among the early miners were Berkelman and Lambert, who worked a deposit on the Barcoo in 1872-1873, and whose opal attracted great interest at the Queensland Annexe of the London International Gem Exhibition in 1873.

By 1875 there had been a number of wonderful finds and interest began to grow, but it wasn’t until, 1888 that Tullie Wollaston , a young surveyor turned entrepreneur from Adelaide made a determined effort to market the gem. In so doing he engraved his name forever across the annals of history. It was due to his sheer determination in convincing the gem merchants of the world to accept the gem that we now have a viable industry.

Opal gougers of last century were mostly shearers and station-hands who had little or no geological knowledge. George Cragg, a young stockman, discovered the northern opal fields on Warronbool Downs 100 kilometres south of Winton where the Opalton Field exists even to this day.

Two World Wars and droughts slowed the progress of Boulder Opal realising its full potential on the world stage. Although mining on a small scale continued it was relatively dormant. It was not until 1967, when Des Burton , a pharmacist from Quilpie become involved with Boulder Opal, unwittingly through his efforts, helped revitalise an industry. In the 1970’s he introduced modern opal cut mining techniques which revolutionised the opal mining industry.

Boulder Opal and the people that mine and deal with opal have supplied the industry a rich and colourful history, which has become part of Australia’s heritage. Opal has been discovered in Queensland from the Southern Borders of Western Queensland to as far north as Kynuna, this probably would be the largest opal field ever known, with opal mining centres in Winton and Quilpie.

Today the Queensland opal miner still exists, supplying the markets of the world with this most exquisite product, Queensland Boulder Opal.

- 1877 – Mining for precious opal in igneous rocks begins at Rocky Bridge Creek, a tributary of the Abercrombie River, in the Central West.

- 1881 – Opal is discovered at Milparinka, near Tibooburra in the Far West.

- 1889 – Precious opal is discovered at White Cliffs.

- 1880s or 1891 – Opal is discovered in sedimentary rock at Lightning Ridge (Wallangulla) and other localities in the area, but its commercial value is not recognised.

- 1890 – Precious opal mining begins at White Cliffs (continuing to 1915 then going into decline).

- 1896 – Opal is discovered at Purnanga and Grenville-Bunker Field. These occurrences are near White Cliffs and so extend the size of that opal-bearing district.

- 1897 – Opal is discovered in igneous rock at Tooraweenah, near Coonabarabran.

- 1901 – Opal is discovered in igneous rock at Tintenbar, on the Far North Coast.

- 1901-1905 – Opal mining begins at Lightning Ridge. The first shaft was put down around 1901 or 1902 by Jack Murray, a boundary rider who lived on a property nearby. Some time later, possibly a few months, a miner from Bathurst named Charlie Nettleton arrived and commenced shaft sinking. It was he who in 1903 sold the first parcel of gems from the field for $30, not a fiftieth of the price that could have been obtained five years later.

- 1908 – Opal mining begins at the Grawin-Sheepyard Field in the Lightning Ridge area, increasing the importance of the opal fields in the district.

- 1919 – Opal mining begins at Tintenbar, continuing to 1922.

- 1920 – The Newfield opal area is discovered.

- 1985 – Seminal work by the Geological Survey of New South Wales leads to better, more scientifically controlled exploration for opals.

- 1989 – The Coocoran opal area is discovered in the Lightning Ridge district.

- 1998-1999 – The estimated value of opal production in the State is about $44 million. New South Wales (and Australia) is a leading world producer of opals.

High altitudes will not affect your opal. The only major things that can damage your opal are impact, extreme fluctuations in heat (e.g. placing your opal over a flame) or extremely low humidity for long periods. Extreme variations in heat cause the opal to expand and contract, causing cracks or crazing.

The name ‘triplet’ refers to the number of layers in the stone, not the number of colours. Triplets consist of a thin slice of opal glued to a black backing, which is designed to imitate black opals. The triplets have a third layer of crystal, glass, or quartz capping to round off the stone and give it a cabochon. ‘Doublets’, on the other hand, consist of two layers – a thin layer of opal and a black backing, with no capping.

If there are any other myths you can think of, or something you’ve heard about which you’re not sure is true, please don’t hesitate to email us and we’ll investigate it and include it in this list!